Table of contents

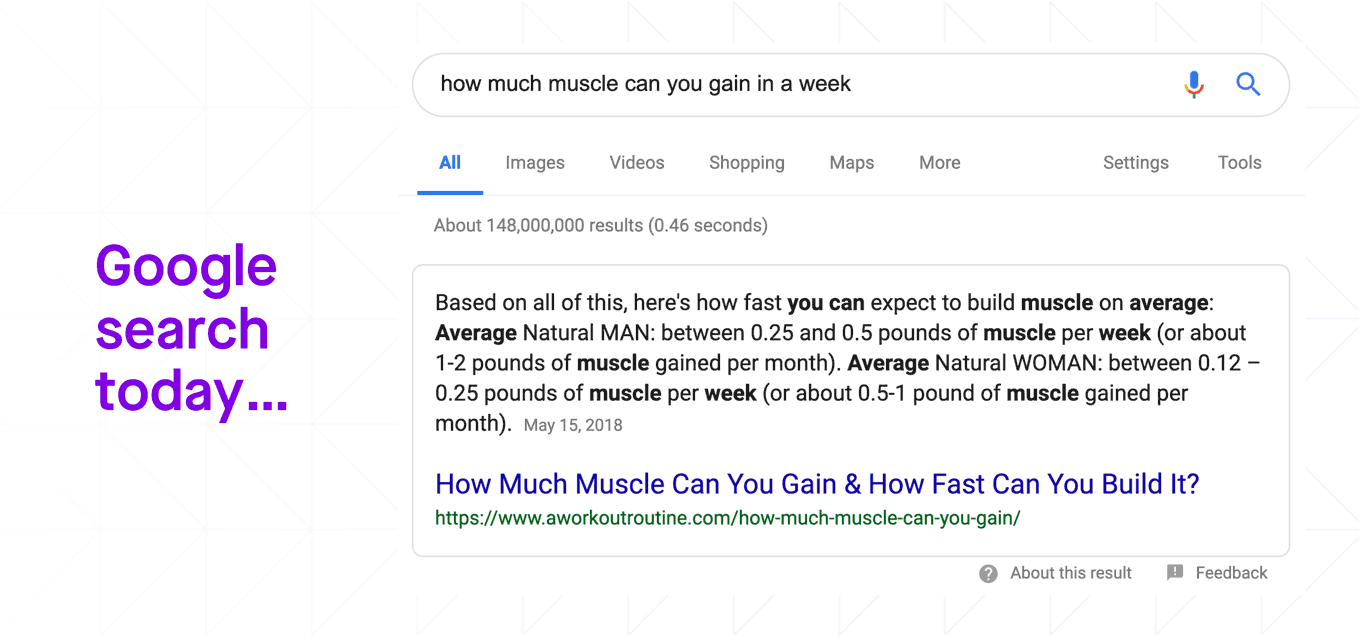

When we talk about search, Google usually comes to mind. If you ask Google “How much muscle can you gain in a week?”, Google not only finds the relevant web page, but also extracts the exact answer in a short paragraph from that web page.

This “featured snippet” style of answer is so useful that Google displays it above all other search results.

Figure 1: Fully-phrased questions make up a growing portion of searches

Figure 1: Fully-phrased questions make up a growing portion of searches

Jiang Chen, one of Moveworks’ co-founders, and I usually refer to these snippets as WebAnswers, which was the project name originally used by Google. We know this style of answer well because we were both founding members of that project at Google. We built that service from the ground up and saw it grow to significantly influence the Google search experience. When we started this project, less than one percent of Google search queries were entered as fully-phrased questions, like the one shown in the example above. Searchers were more accustomed to entering clusters of keywords. But after introducing WebAnswers, we saw a steady shift in the phrasing of search queries as people switched to posing more long-form questions, and relying less on keywords. In fact, featured snippets are now provided for about 12% of Google search traffic. This proved to be one of the first and most successful applications of natural language understanding (NLU) in consumer search technology.

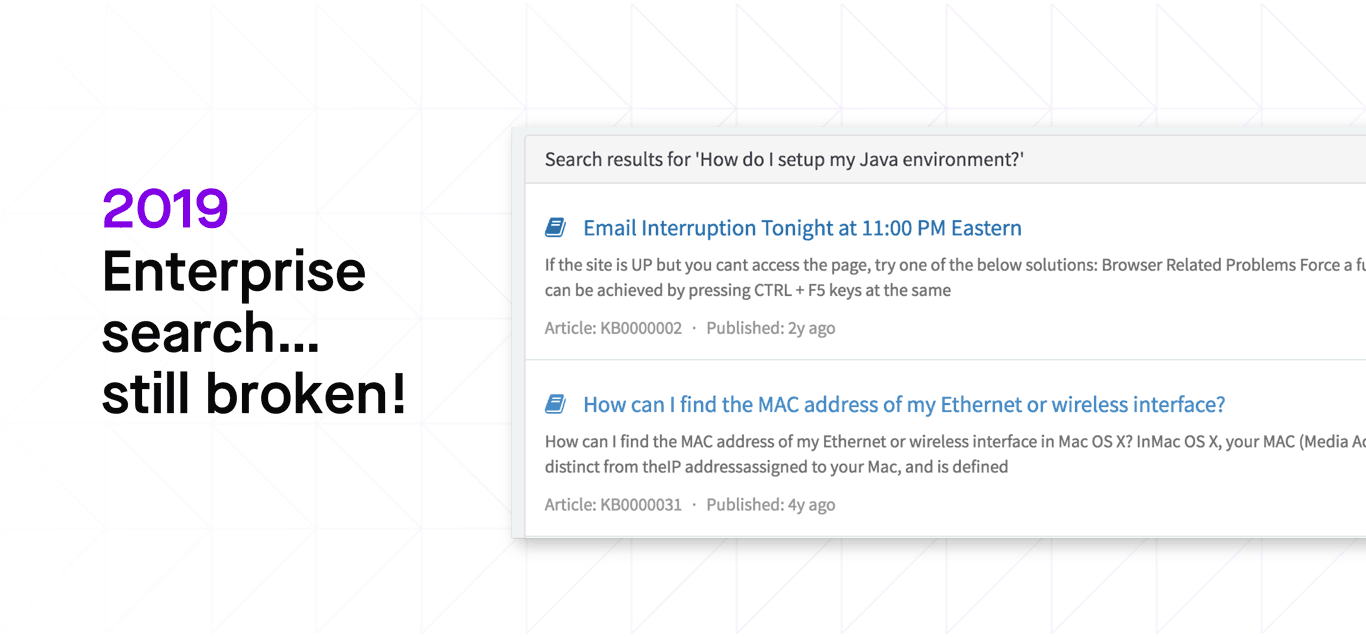

Consumer search hasn’t always been a great experience, but in the last two decades, it’s come a long way. Now you can type a question, and get an answer. Simple. But what about enterprise search? Unfortunately, that’s still broken.

Figure 2: In the enterprise, most search tools remain primitive

Figure 2: In the enterprise, most search tools remain primitive

For example, if you search an enterprise knowledge base for “How do I setup my Java environment,” you’ll struggle to find the relevant article, and you’ll often get seemingly random results, such as email interruption notices or advice on finding your MAC address.

So, why is enterprise search still broken? Well, the enterprise setting presents challenges that make search a very hard problem!

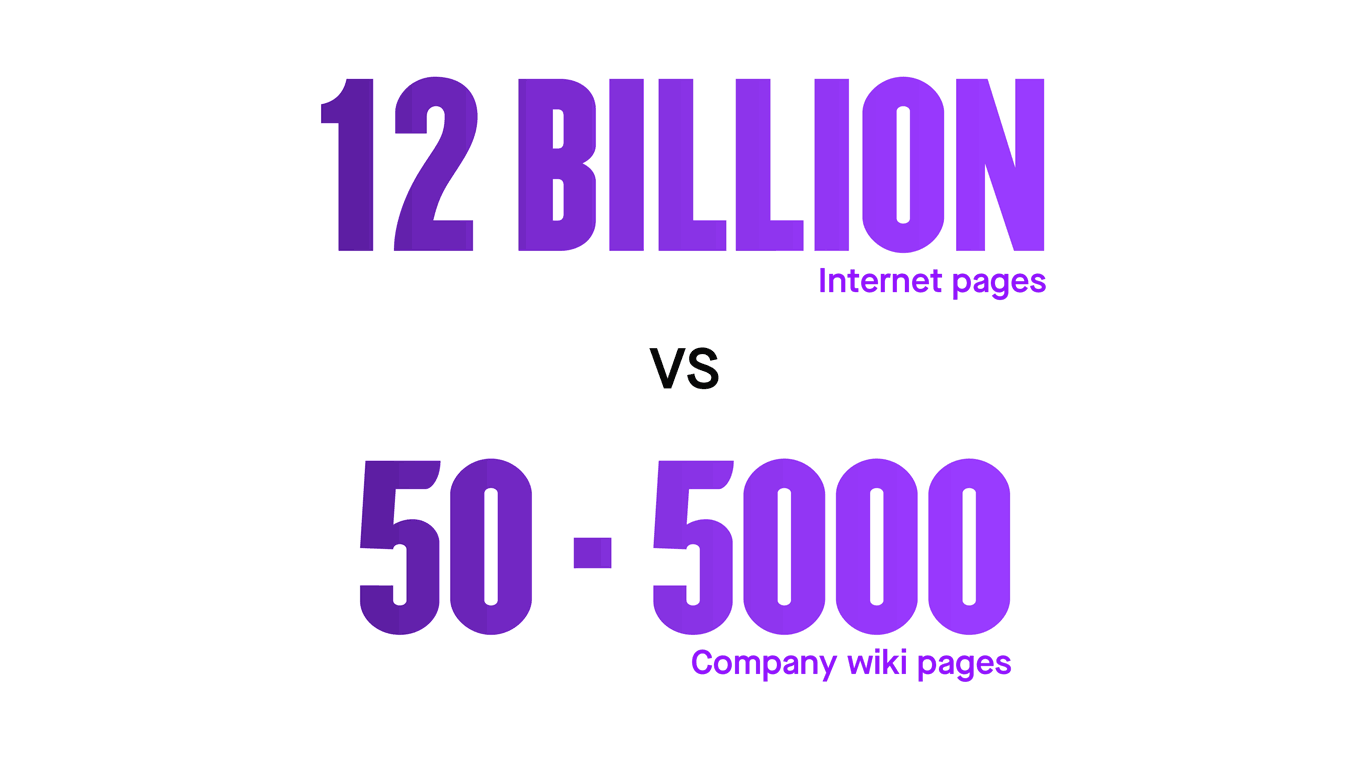

Consumer search engines like Google have access to at least 12 billion pages on the Internet. Almost every answer repeats itself, in one form or another, on multiple pages across the web. These similar pages reinforce the search result relevance.

On the other hand, a typical company wiki or knowledge base might contain only 50 to 5,000 pages. Usually the answer appears only once — as a paragraph, a sentence, or even a phrase. So the task of enterprise search is vastly different from consumer search. For enterprise search, it’s like trying to find the only needle in a haystack.

Figure 3: In the enterprise, there is less data to mine

Figure 3: In the enterprise, there is less data to mine

Another advantage consumer search engines have is the wealth of user interactions. Billions of users scroll and click search results, and this activity provides vital signals that help the search engine make relevance judgements.

Enterprise search engines, by contrast, usually have sparse usage that cannot function as a reliable input for article relevance.

Existing approaches are primitive, and employees don’t get useful answers

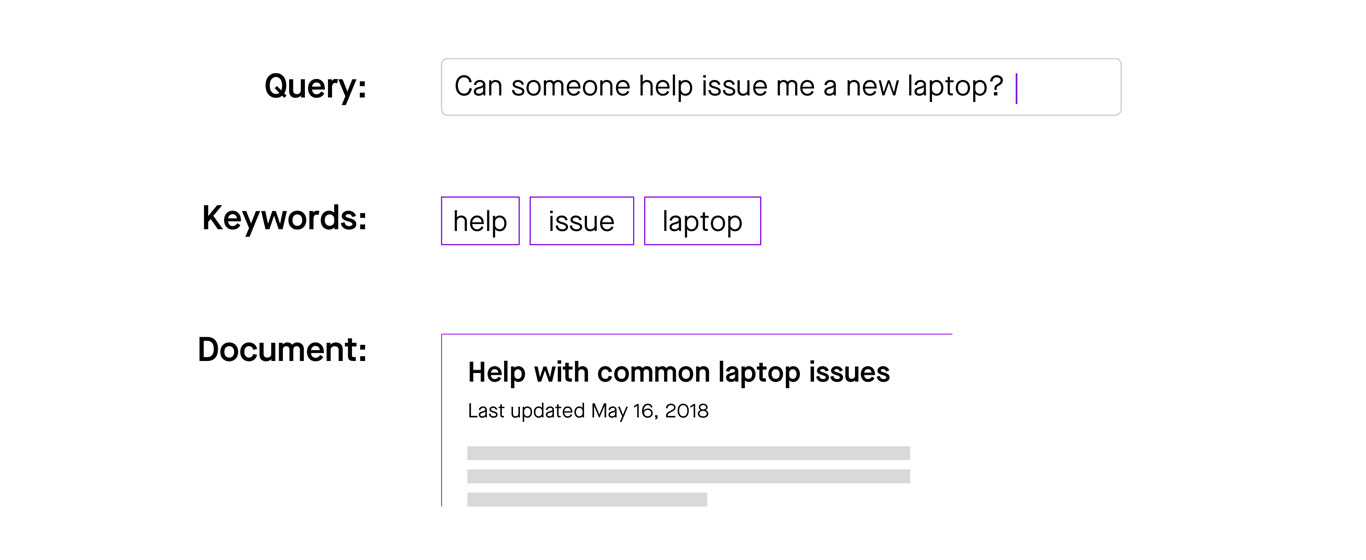

Although enterprise search is a hard problem, many enterprise search systems still rely on primitive models in an attempt to find relevant knowledge articles. Of these primitive models, keyword tagging is the most common. This involves the author of an article or wiki page adding keyword meta-tags.

But keyword tagging is incredibly brittle, and requires significant manual effort and judgement. Consider the query “Can someone help issue me a new laptop”. If the knowledge writer had earlier added the keyword tags “help,” “laptop,” and “issue” to the “Help with common laptop issues” article, then that article — and not the one about ordering a laptop — would be wrongly served up as the response to the request.

Figure 4: Keyword tagging is brittle

Figure 4: Keyword tagging is brittle

Keyword tagging is brittle because it ignores syntax. That is, it considers each word in isolation, without regard to its grammatical role in the sentence or phrase. Consider these three sentences:

- What is the process to order a monitor?

- I need to monitor the order process.

- I can’t process a monitor order!

If we rely on keywords without considering syntax, these three sentences become indistinguishable. But the syntax tells us that “monitor” describes an object in the first sentence, an action in the second sentence, and a type of order in the third sentence. Syntax is really important for understanding context.

A second reason keyword tagging is brittle is that it ignores semantics. Semantics refers to the meaning of the word, phrase or sentence.

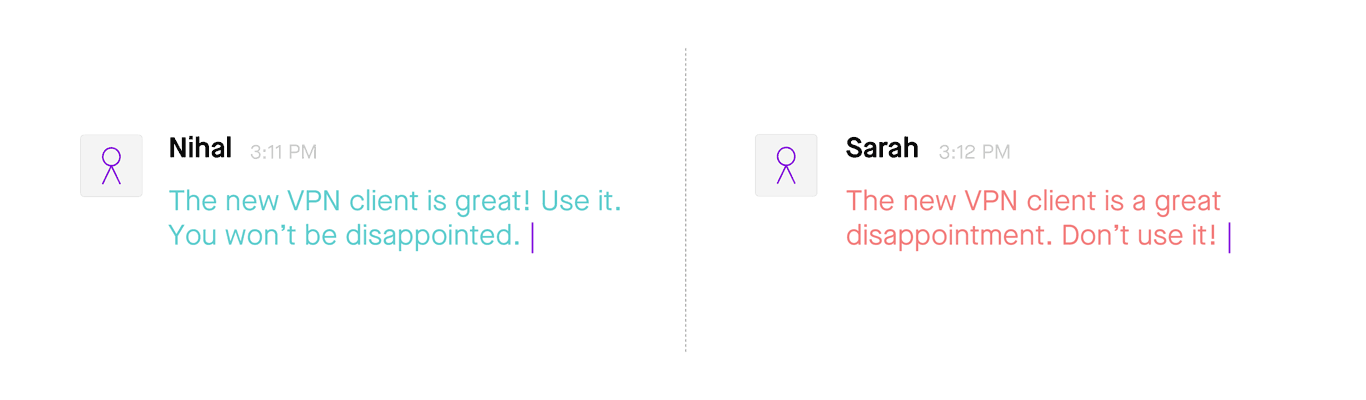

Figure 5: Keyword tagging ignores semantics

Figure 5: Keyword tagging ignores semantics

The two sentences in this example have totally opposite meanings but contain very similar words. Keyword tagging falls apart here because it cannot capture the semantic meaning of the words.

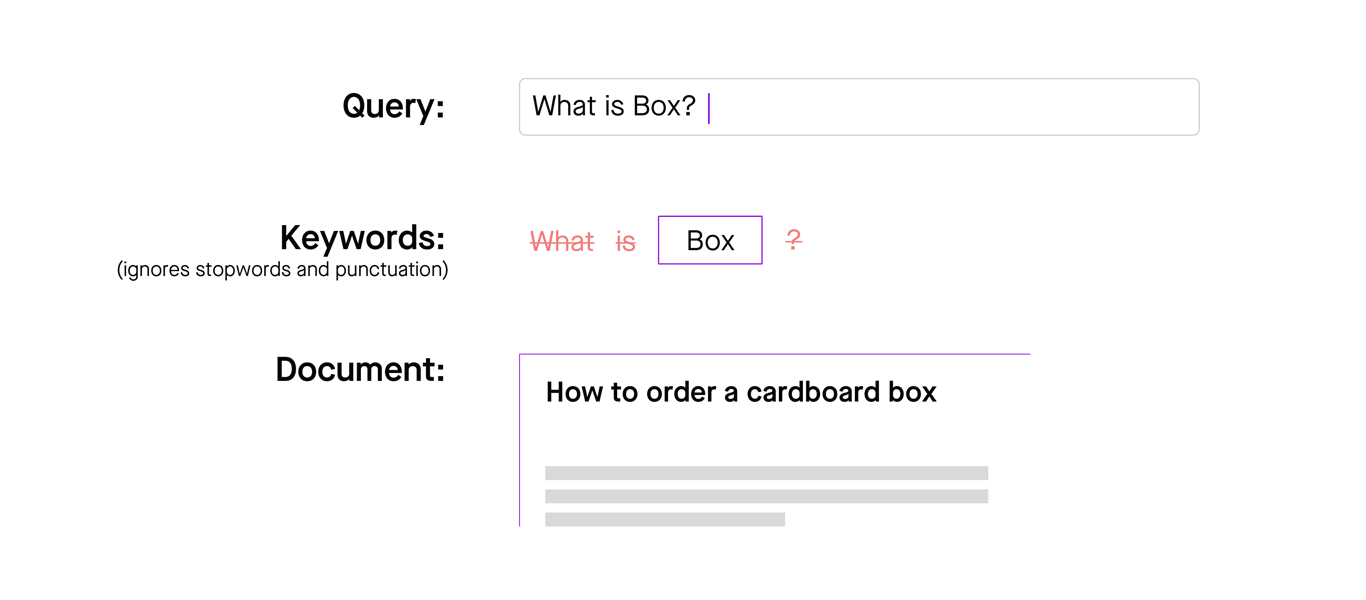

Most keyword-based search systems are configured to ignore certain words (often referred to as “stop words”) because those words sometimes carry less meaning. Keyword search also ignores punctuation marks. But stop words and punctuation are useful in understanding the meaning of a word or phrase, so when a keyword search ignores them, it reduces the quality of the results.

For the query “What is Box?”, there is only one keyword; “Box.” By only analyzing the keyword, it’s hard to tell whether the underlying search query is asking for a definition of Box, instructions for using Box, help provisioning Box, or troubleshooting advice. Without this information, we can get hilarious (albeit frustrating) search results.

Figure 6: Keyword-based systems can’t distinguish between multiple meanings of a word

Figure 6: Keyword-based systems can’t distinguish between multiple meanings of a word

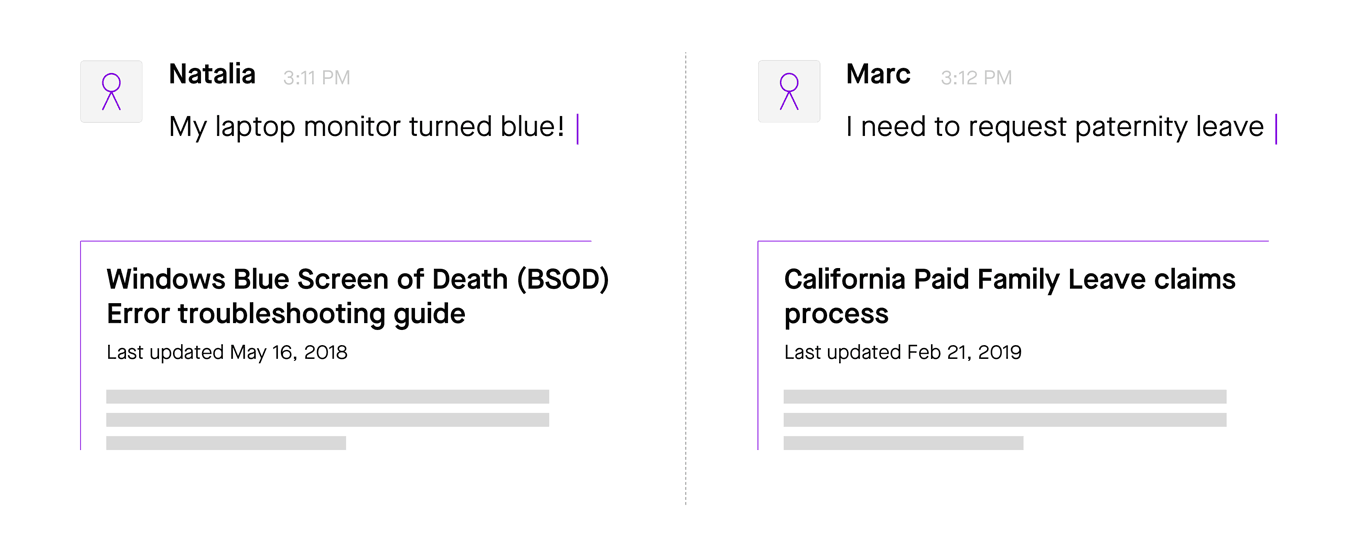

Another common trait of enterprise language is that it is often symptomatic in nature. And the vocabulary someone uses to describe the symptom can differ a lot from that used to describe the solution. Again, keyword tagging really struggles here.

Figure 7: In the enterprise, employees tend to describe symptoms

Figure 7: In the enterprise, employees tend to describe symptoms

Between the question “My laptop monitor turned blue” and the answer “Windows blue screen of death (BSOD) error”, the only overlapping keyword is “blue”, which is pretty generic. So you’re probably not going to find this answer with this search query. You might also notice that the question is phrased more like a statement — this is very common in employee support scenarios where employees often don’t know exactly what they need.

How Moveworks delivers modern enterprise search

At Moveworks, we have invested a lot of time and energy in fixing enterprise search by applying cutting-edge natural language understanding and machine learning techniques. Key to our approach is not just digging up articles, but finding precise answers in the form of single sentences, bulleted lists, or paragraphs buried deep within existing knowledge articles, documents, and FAQs.

So how do we do this?

Understanding the question

To understand what a user is asking for, we have to treat their questions as complex language, not just as clusters of keywords. We employ many machine learning techniques to analyze syntax, structure, and semantics.

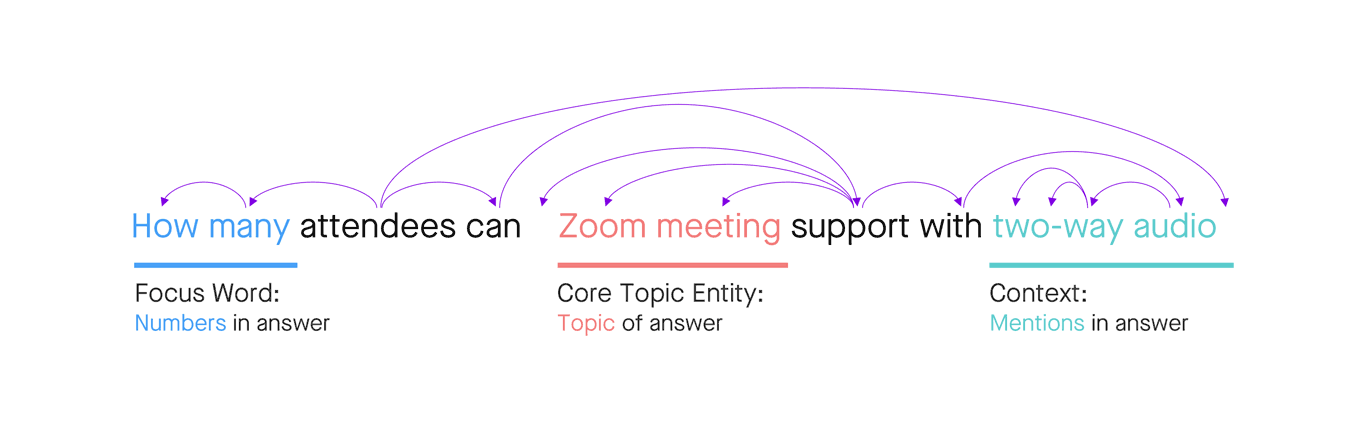

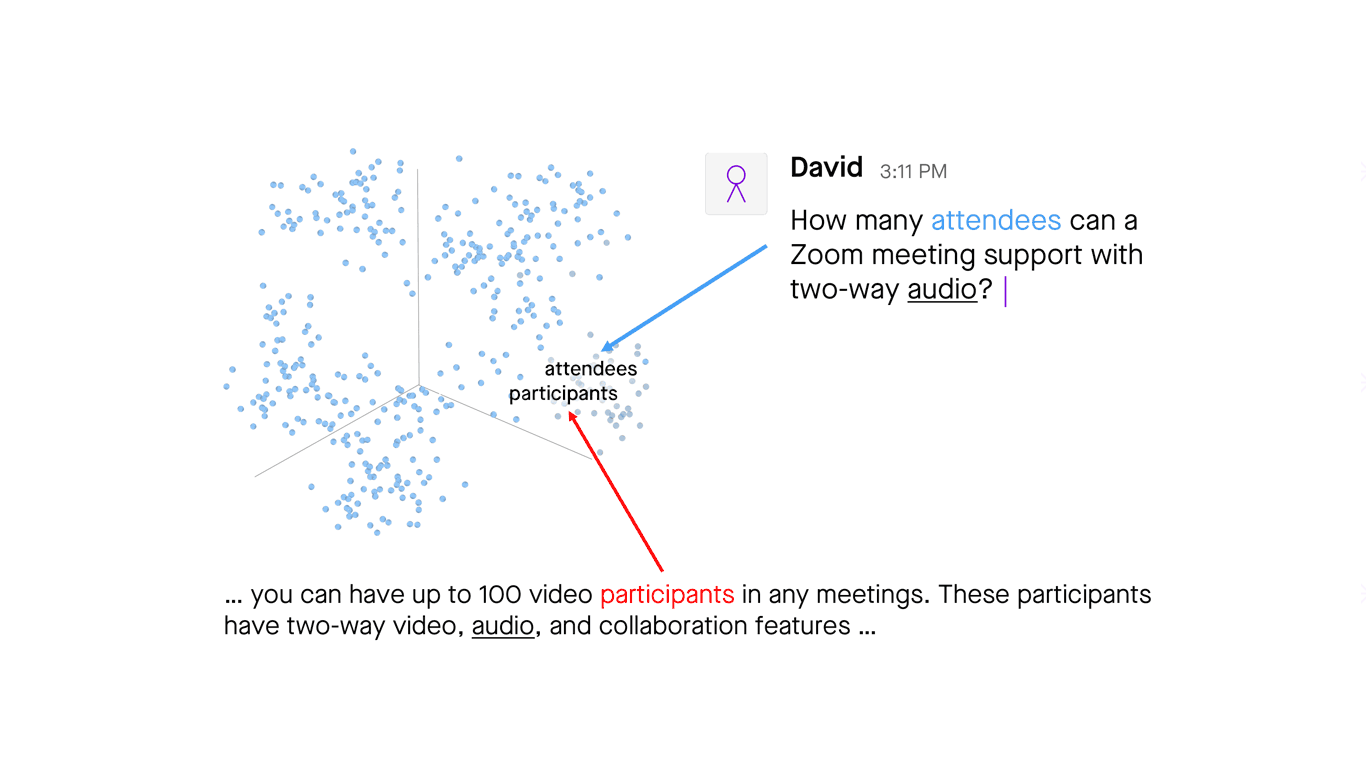

Figure 8: Machine learning analyzes syntax, structure, and semantics

Figure 8: Machine learning analyzes syntax, structure, and semantics

In this example, by understanding the syntax, we know the focus word for this question is “how many.” By using dependency parsing, which is a machine learning technique of extracting grammatical structure and defining relationships between words, we know the core topic entity is “Zoom meeting,” and we know the topic needs to be framed in the context of “with two-way video.”

Understanding question language in this way helps not only to understand the meaning of the question, but also to set our expectations for an answer. In this case, we’re expecting to see an article that:

- addresses the topic of “Zoom meeting”;

- contains numbers to address the “how many” focus word; and

- mentions “two-way audio.”

Synonymous words and phrases

Word embedding and sentence embedding are two important machine learning techniques that use deep neural networks to better assess the meaning of a piece of text. Word embedding uses mathematics to plot words on a massively multi-dimensional graph relative to other words on the graph. The location of the words in the graph can be based on any attribute of the word, such as what words tend to precede it in a sentence, or how often it shows up in chat messages. We refer to this as projecting words into a common semantic space. Using this approach, semantically similar words and phrases naturally cluster together. The same approach can be used for sentences, in what we call sentence embedding.

Figure 9: Word embedding is a technique for finding relationships between words

Figure 9: Word embedding is a technique for finding relationships between words

A key output of embedding models is the ability to identify synonymous words and phrases in order to help a search system cross the infamous lexical gap, which refers to the vast difference in the way that questions are structured, compared with their answers. For example, I might have a question about how many attendees I can invite to a Zoom video conference, but a simple search for "attendees" fails to yield an answer because Zoom refers to users as "participants." Through the use of word embedding, our search system knows those two words refer to the same thing.

Understanding synonymous words and phrases also helps us to figure out alternate queries. If you’ve ever entered something into a search bar, struggled to find an answer, then rewritten your search using different terms and consequently found what you’re looking for, then you’ve experienced the benefit of alternate queries. This is particularly important in enterprise search where, as we’ve discussed, answers are in sparse supply.

Figure 10: Alternate queries are other ways to phrase the question

Figure 10: Alternate queries are other ways to phrase the question

To do this we combine the outputs of word and sentence embeddings with sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) machine learning techniques. These techniques allow us to “encode” a piece of text in one format and then “decode” it in another. It’s a popular technique for language translation where you might “encode” English language text and “decode” it in Spanish. Here we use it to figure out the multitude of different ways a question could be phrased.

By applying this method, we can discover that “My laptop won’t power up” is somewhat synonymous with “My laptop won’t start,” “My Lenovo won’t turn on”, “Computer not starting,” and so on. And with all these additional search terms, our ability to find a relevant answer increases significantly.

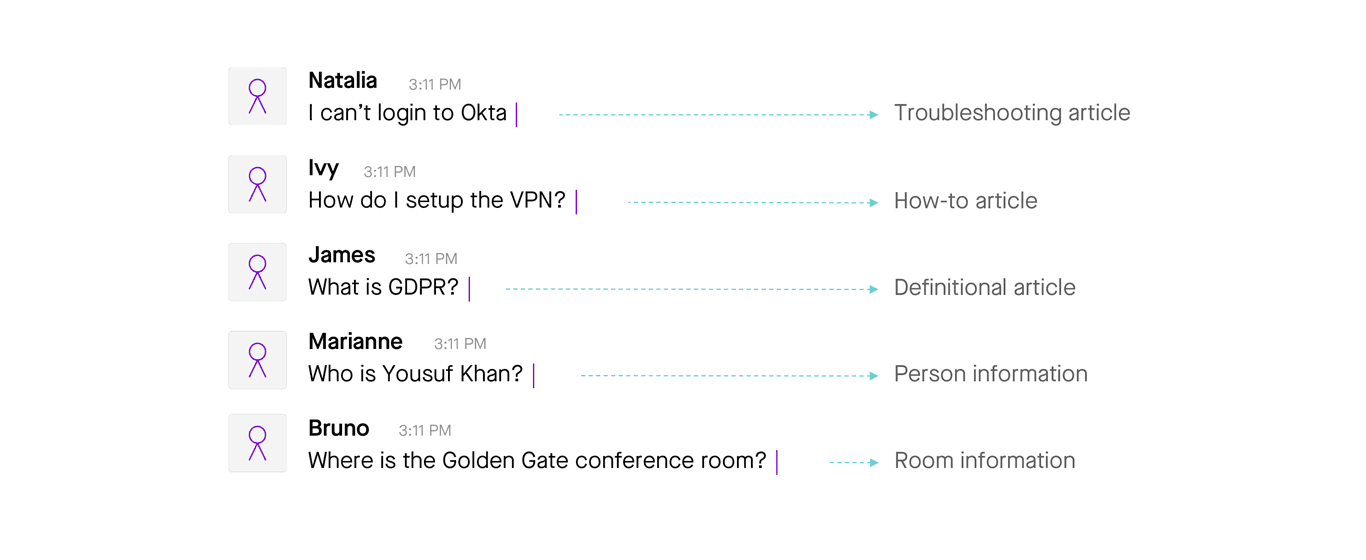

Query typing is another machine learning technique that helps an enterprise search system take incoming text and understand what type of question or statement it is, so that the system can better predict which solutions or knowledge articles are most likely to be relevant. Query typing machine learning models are able to interpret a symptomatic statement like, “Excel just crashed again” and recognize that it’s a request for troubleshooting guidance. Or that “VPN setup instructions” is most likely a request for a how-to article.

The trick here is using the syntax and semantics of the question to predict what form the answer should take. This serves as an important input to ranking models to help make more accurate predictions about the relevance of an answer.

Figure 11: Query typing identifies what sort of question or statement the employee has typed

Figure 11: Query typing identifies what sort of question or statement the employee has typed

None of this is possible in a keyword matching-based search system. To make accurate predictions, machine learning is a necessity.

Understanding the answer

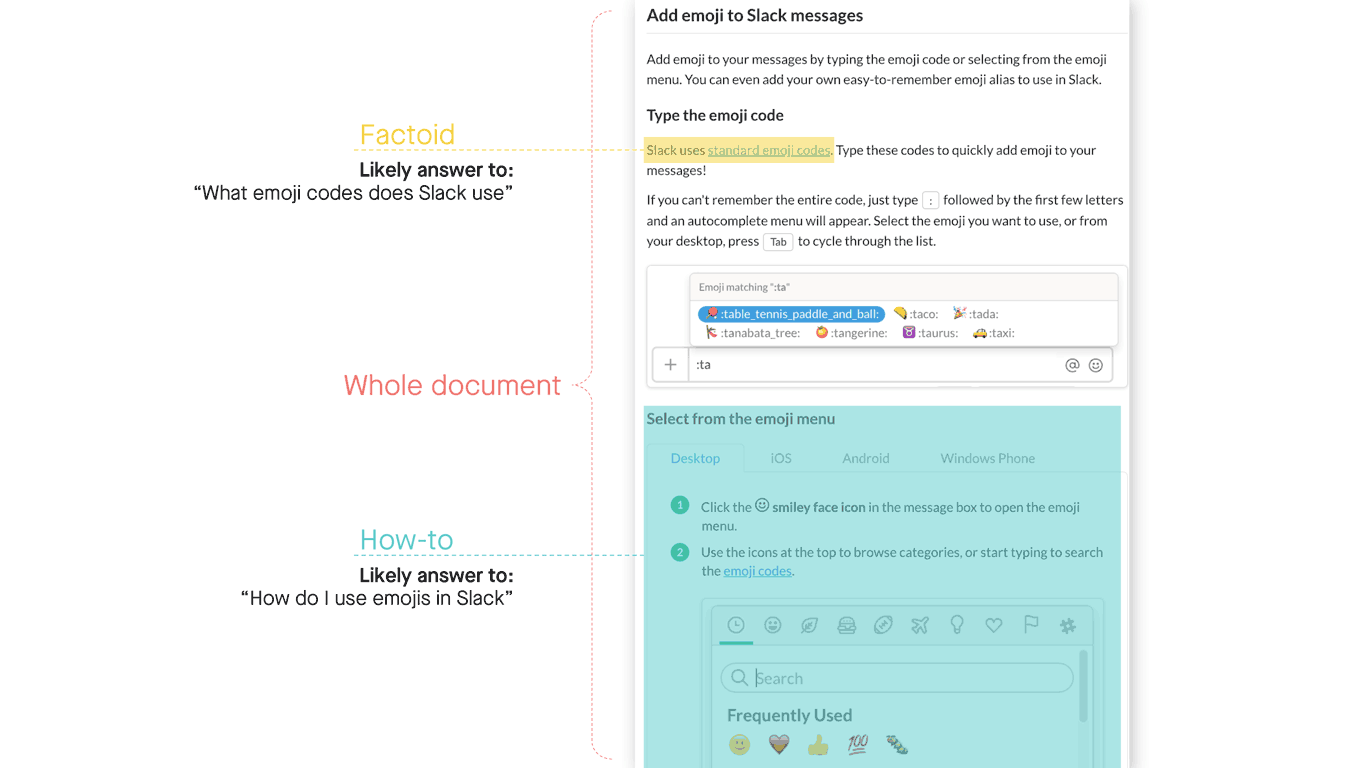

Knowledge articles in the enterprise can be long, and they often aggregate many things under a common topic. For a reader, this makes it difficult to find the most relevant part of an article to address their specific issue or request. Similarly, for a search system, it’s challenging to assess the “meaning” of an entire article when it may contain many independently useful facts.

Our approach to solving this problem is to divide and conquer long knowledge articles by dissecting them into snippets, much like Google does with web pages. Snippets can come in many forms — short paragraphs, bulleted lists, images with descriptors, single factoid sentences, and so on — so we developed machine learning models that recognize the content, context, and presentation of information, enabling our algorithms to automatically create the right type of snippet for each answer.

Figure 12: Dividing a knowledge base article into answers, or snippets

Figure 12: Dividing a knowledge base article into answers, or snippets

Earlier I discussed using Seq2Seq to discover alternative ways of phrasing a query. We apply the same approach for snippets to generate alternative phrases for answers. And much like query typing, we also use answer typing models to identify what type of question this answer will best address. The goal of all of this is to generate as many different signals and insights about questions and answers as possible, so we can more accurately match them.

Matching questions to answers

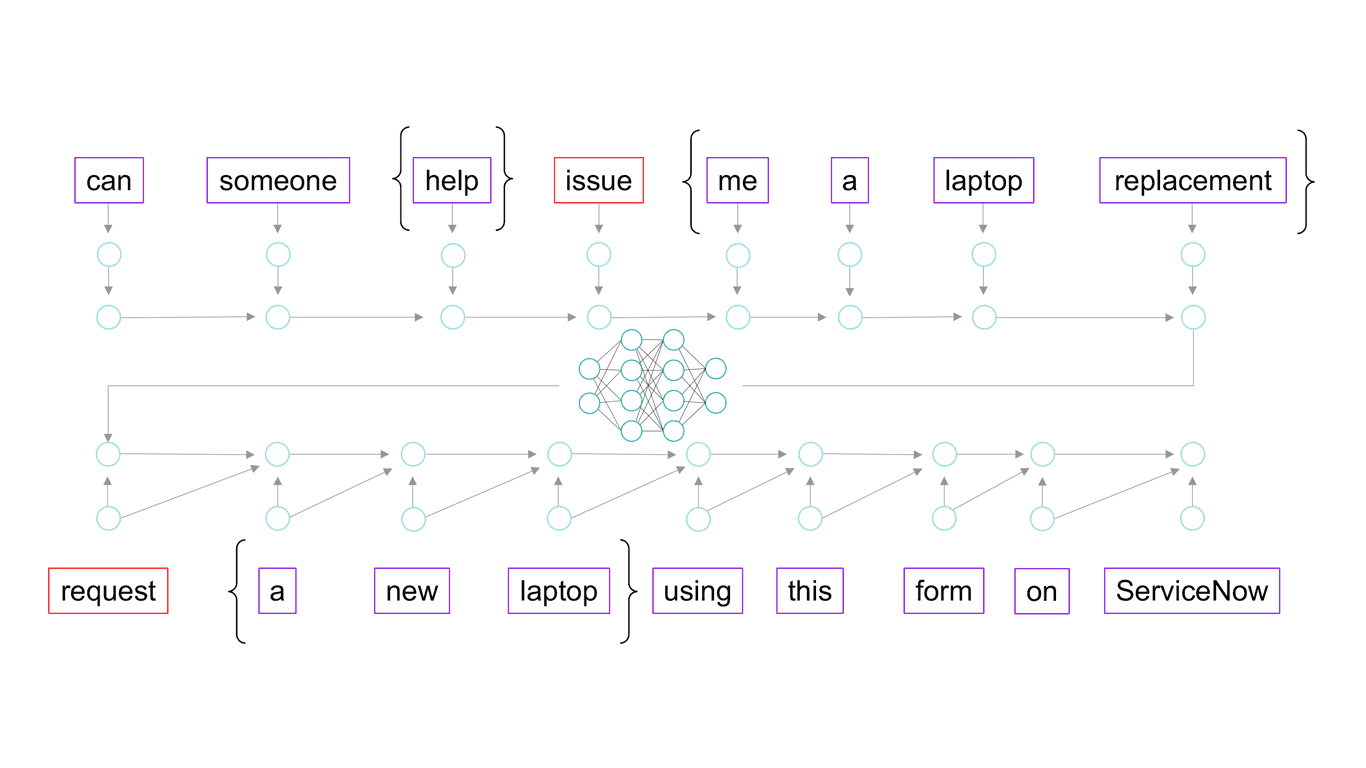

Once we have a good understanding of both questions and answers, we use machine learning to match them. We use a lot of different machine learning techniques here (too many to discuss in this article) but Seq2Seq is a key contributor again.

By training a neural network with tens of millions of examples of questions and answers focused on a specific domain, like enterprise IT, we can use Seq2Seq to predict questions for which a given snippet could be an appropriate answer, or predict what text we might find in an answer for a given question. Essentially we are asking the model “if this is an answer, what question would it answer?”. You can start to see why a model that made its name in language translation is so useful here — we are translating between questions and answers.

Figure 13: Seq2Seq techniques help map questions to answers

Figure 13: Seq2Seq techniques help map questions to answers

One of the amazing aspects of this model is that it's very good at putting words into context. Let’s look at the example shown above:

- the question contains the word "issue" sandwiched in between "help" and "me a laptop"

- the answer contains the word "request" followed by "a new laptop"

The Seq2Seq neural network recognizes the relationship between the word “issue” in the context of the question, and the word “request” in the context of an answer. Likewise, it sees that "replacement" in the question and "new" in the answer are probably referring to the same thing. This is very powerful because neither the words nor the sentences are visibly similar, but the model has discovered the relationship nonetheless.

Assembling an enterprise search system

Solving enterprise search is not a trivial matter. There are many aspects of enterprise search that make it more complex than consumer search. But machine learning and natural language understanding have finally made it possible to answer ambiguous, symptomatic search queries with precise, accurate snippets of information retrieved from sparse knowledge bases.

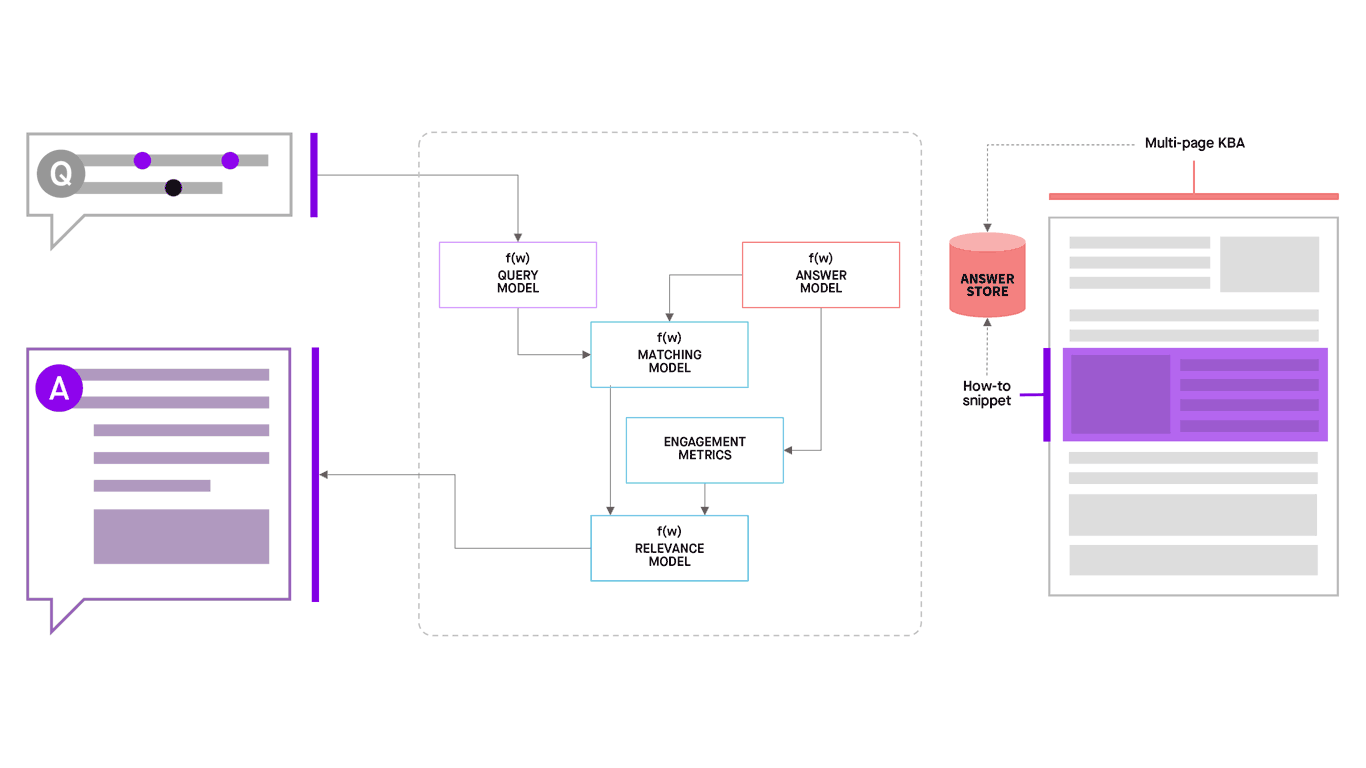

Here are the key ingredients to the Moveworks semantic search system:

- Knowledge ingestion: We start by ingesting long-form knowledge articles from available knowledge bases

- Answer store: From these, we extract useful snippets and index them in an answer store

- Answer model: We then use several machine learning techniques to understand the semantic meaning of the answer, identify what type of answer it is, discover synonymous phrases, and predict what questions might match with it

- Query model: We analyze the query to identify focus words, topics, context, synonyms/related words, possible alternative forms of the question, and likely answers.

- Matching model: This model uses available insights from the query model and the answer model to identify candidate snippets.

- Relevance model: Considers all of the signals, data, and candidate snippets and identifies the most relevant snippets to be returned as likely answers.

Of course, the really hard part in all of this is returning these answers in less than 100 milliseconds via a chatbot. But we’ll save that for another post.

Figure 14: Finding answers for questions

Figure 14: Finding answers for questions

Finally: Conversational search in the enterprise

As a company focused on solving IT support issues using AI, we spend a lot of time looking at the types of issues raised or questions asked by employees in the enterprise; search does not address everything. We’ve had to build many different techniques to address employee needs like unlocking accounts, provisioning software, creating email groups, and other requests that require end-to-end automation rather than answers. But search is a critical part of the support experience for employees: typically, about 1 in 3 support issues are troubleshooting or information-seeking in nature.

Despite the demand, enterprise search has lagged far behind consumer search for too long. It's been hard to use and is prone to embarrassing failures. There are good reasons why we’ve not seen much progress: while a deep trove of usage data helps hone consumer search results, for enterprise search, this usage data is hard to come by, so enterprise search has relied instead on keyword tagging, which is primitive; employees often describe symptoms only, resulting in a big gap between how questions are asked and what text appears in answers; and we typically don’t have good data on usage, interaction, or freshness of knowledge articles.

Moveworks has met these challenges by applying NLU and advanced machine learning to tackle enterprise search in a unique way. This has not been easy — we’ve had to embrace and develop many novel techniques to overcome the constraints of the enterprise — but the end result is magical. I look forward to sharing more about our approach, technology, and the impact of our enterprise search capability in future articles.

Interested in learning more?

To learn more about why NLU matters for IT, and how it helps deliver enterprise help more quickly and more easily, see our posts: