Table of contents

For those who follow the tech world, hardly a week goes by without the news of another domain conquered for good by machining learning (ML). From IBM Watson’s victory over human Jeopardy champions in 2011, to DeepMind's defeat of the world’s best Go players in 2016, to Libratus’s win against millionaire poker pros in 2017, ML is redrawing the boundaries of the possible in math, logic, and strategy.

Yet one of the last frontiers left for machines to demystify — the nuances of language — has long remained an uncrackable code.

The result? While ML automates routine tasks across nearly every industry, those that require language comprehension still tend to be performed by human professionals, creating busy work for them as well as frustrating delays for all involved. The complex way that we communicate with one another simply cannot be reduced to fixed rules, decision trees, and other hard-coded strategies that previous language understanding models have employed.

Figure 1: Unlike math problems that computers can approach as a series of discrete operations, the meaning of a sentence can’t be gleaned from its individual words without context.

Figure 1: Unlike math problems that computers can approach as a series of discrete operations, the meaning of a sentence can’t be gleaned from its individual words without context.

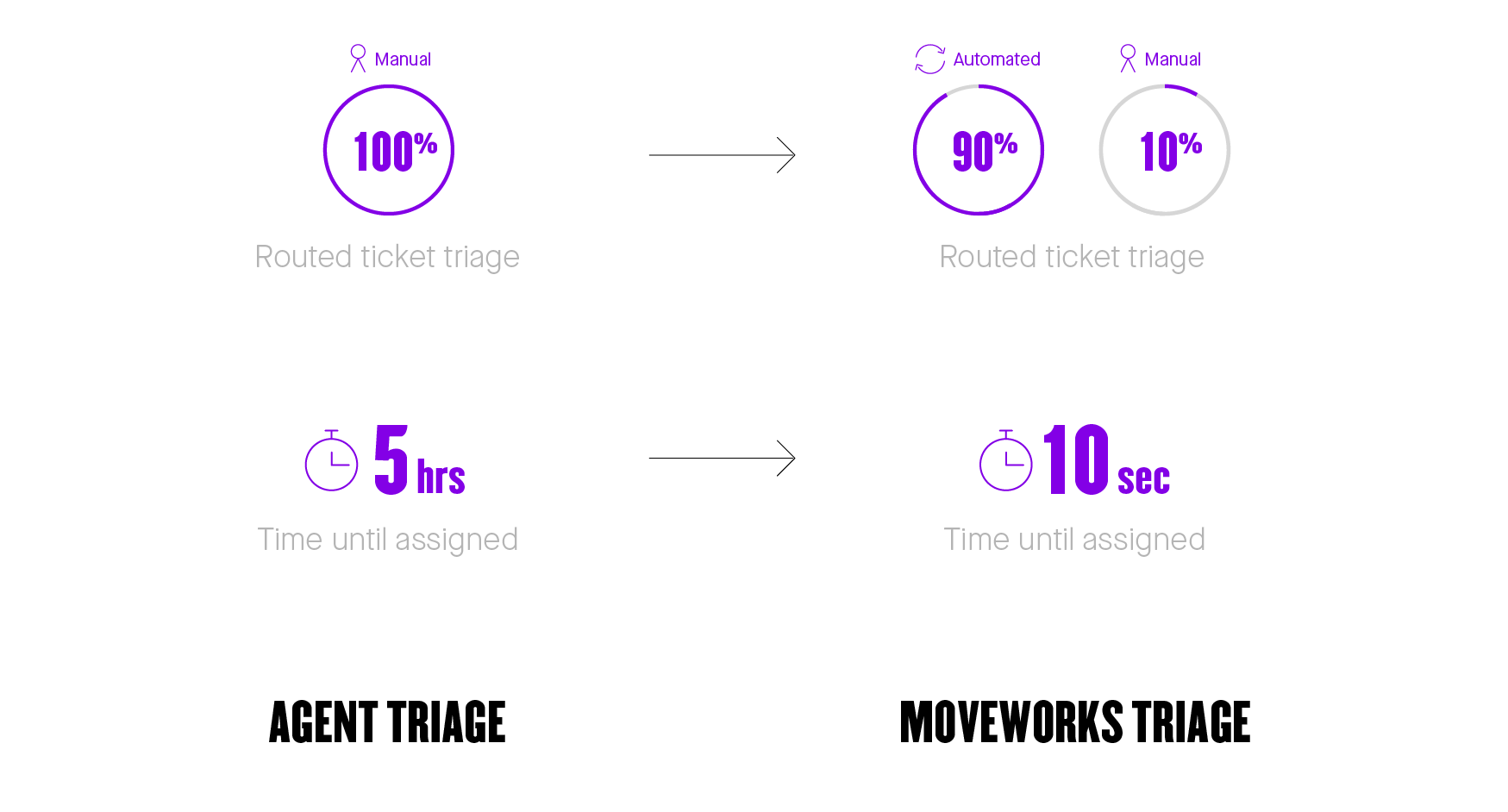

A notable example here is the challenge of routing IT support tickets to the right subject matter experts. As I discussed in Part 1 of this series, the average IT ticket sits in a queue for five hours before a help desk agent first looks at it, at which point the agent must decide which among hundreds of specialized “assignment groups” is the correct one. This anachronistically slow and error-prone process is an obvious candidate for a machine learning solution, yet past ML-powered attempts at automated triaging were unsuccessful for the reasons listed in Part 1:

- Lack of context: Early ML models for automatic ticket triage tended to learn only from tickets’ short descriptions and one or two other inputs, ignoring a mountain of useful data.

- Reliance on guesswork: Absent the ability to analyze all the information in a ticket, these early models forced the service desk team to guess ahead of time — and without sufficient knowledge — which fields would be the most predictive.

- Small data conundrum: By only ingesting tickets from a single IT service desk, these models failed to capture enough information to make effective routing decisions.

- Not grouping words by meaning: Without grouping each word by its broader category or attempting to understand its meaning in context, classical ML models couldn’t capitalize on the predictive power of employees’ descriptions.

In the sections below, I’ll explore how we overcame each of those sizable obstacles by synthesizing a number of new approaches to ML, including bleeding-edge techniques like BERT. Ultimately, after years in the making, ML can now triage IT support tickets with better than human-level accuracy — and at machine speed.

Learning from your tickets

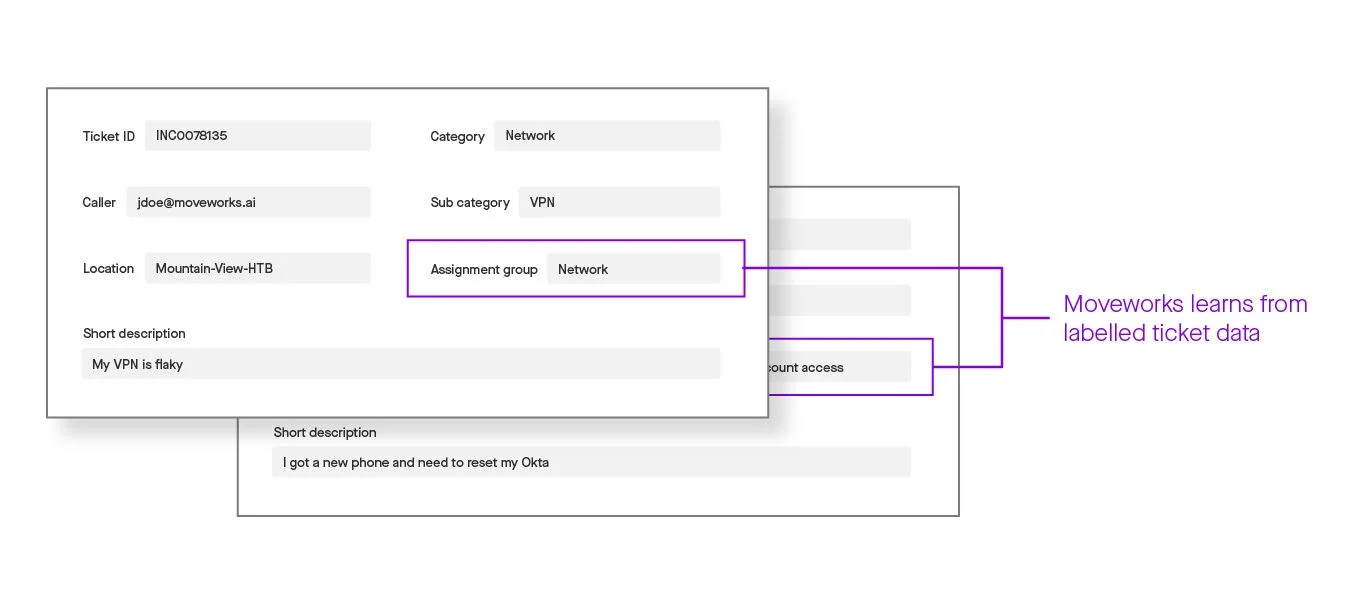

At a high level, automated ticket triage entails correlating an IT ticket’s various fields with the assignment group that can best resolve the issue — exactly what help desks are trained to do. Enter deep learning: a family of ML based on artificial neural networks (ANNs) that emulate the variable connections our brains form over time between related concepts, albeit in a more formalized fashion. To train neural networks, Moveworks uses supervised learning, which includes the following operations:

- Analyze labeled historical data, known as training data. Labeled data means that the correct output values — in this case, the right assignment group for a given ticket — are known in advance.

- Identify which input values we can read and then correlate with the relevant outputs.

- Train a model that uses these known input-output relationships to predict future, unknown outputs.

Figure 2: After learning from labeled tickets, Moveworks’ models can then make predictions about unlabeled data.

Figure 2: After learning from labeled tickets, Moveworks’ models can then make predictions about unlabeled data.

Needless to say, supervised learning depends on a historical set of tickets that are accurately labeled. That’s why — before supervised learning begins — Moveworks validates both that the historical tickets have indeed been labeled consistently and that machine learning is the right solution to the problem at hand. In rare cases, we see an erratic distribution of labels for a given field, which prompts us to work with the service desk team to identify the problematic areas and suggest ways to improve the quality of the labels.

Finding clarity in context

While that all sounds straightforward enough, in practice, any individual field of an IT ticket is likely insufficient to determine the proper assignment group on its own. And as the number of fields increases, so too does the complexity of the computations involved. As we saw in Part 1, classical machine learning models were able to read just a few fields and struggled to transform them into useful outputs. Fortunately, the unprecedented computational power of deep learning today enables us to analyze every field of an IT ticket, as well as metadata like the time it was submitted and the department of its author.

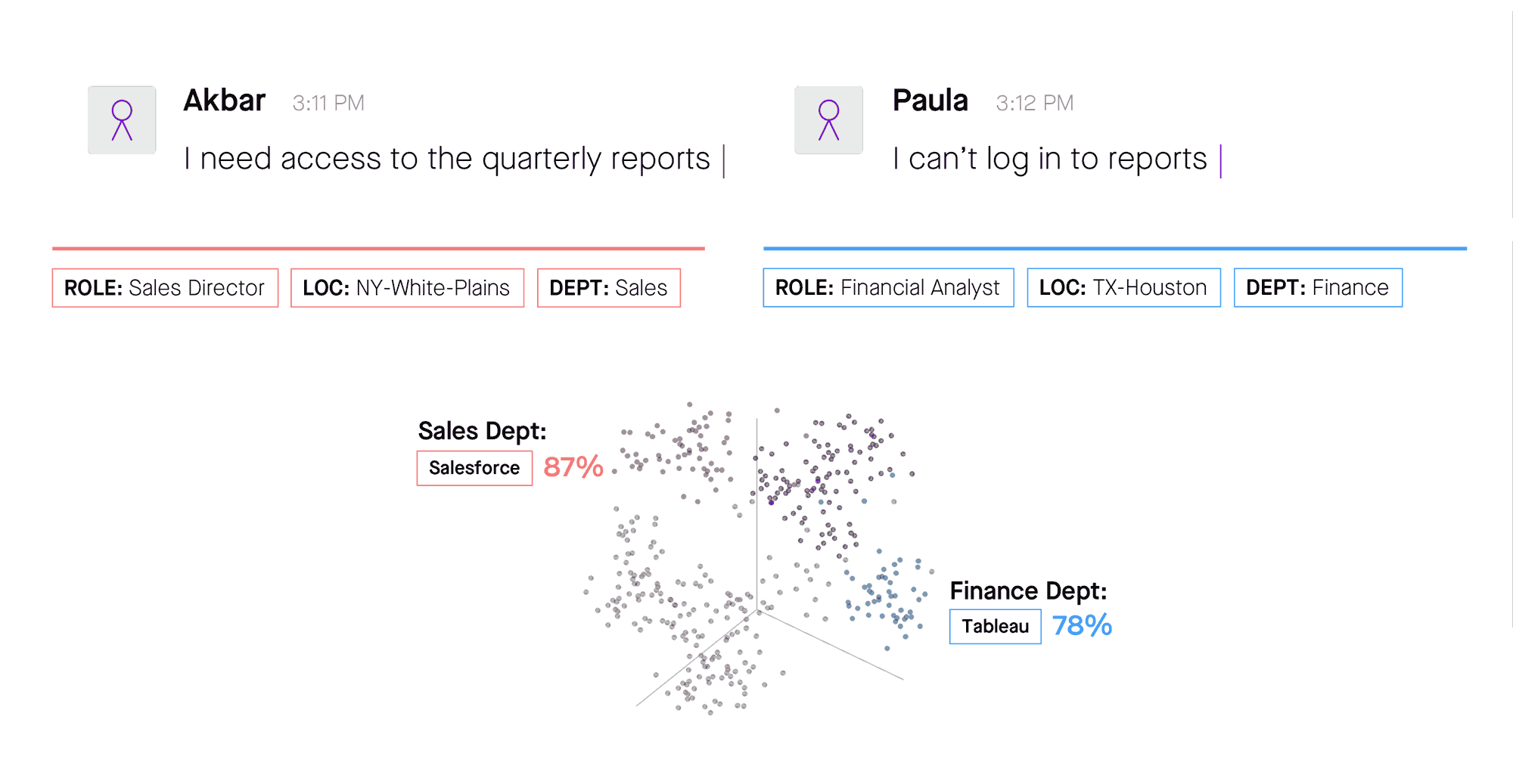

But why is that context important? Couldn’t an automated triaging tool assign each ticket to the correct assignment group based on the keywords in their short descriptions, without worrying about other fields or metadata? To answer that question, consider the situation below, where two employees have submitted similar-sounding tickets that classical models would interpret as identical requests. Based on the additional context furnished by the fields Role and Dept, Moveworks recognizes that the sales director’s request belongs in the queue for Salesforce provisioning, while the financial analyst is having an issue with Tableau. It is this difference that makes context indispensable.

Figure 3: Historical tickets submitted by employees in the same department help Moveworks differentiate between these requests — facilitating not only ticket routing but also resolution.

Figure 3: Historical tickets submitted by employees in the same department help Moveworks differentiate between these requests — facilitating not only ticket routing but also resolution.

From guesswork to knowledge

Of course, the ability to analyze so much contextual ticket data comes with its complications. With this feast of information to digest, how can we hope to separate the signal from the noise? One thing we do know is that human beings are ill-suited for the job. Consuming 50-100 data points, rapidly determining their relevance to a particular IT issue, and then routing that issue to one of hundreds or thousands of assignment groups is overwhelming for service desk agents. Doing all of that in three seconds, meanwhile, is humanly impossible.

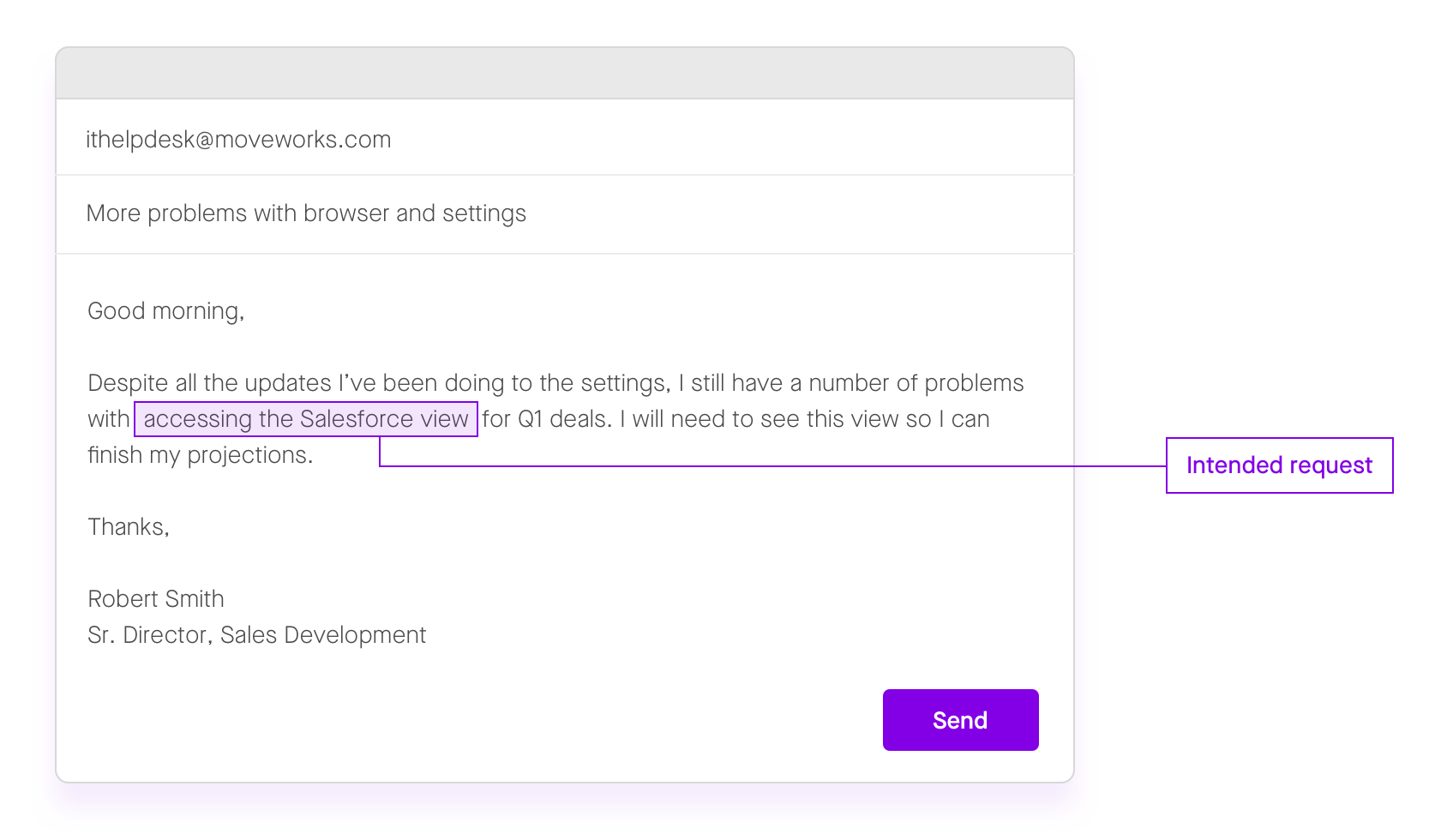

Yet even machine learning models are prone to miss the needle in such an enormous haystack, as we explored in Part 1. Grasping just a single, literal sentence requires is incredibly complex — let alone the task of understanding how that sentence is altered by its broader context. Imagine trying to train an ML model to find the intent of this ticket:

Figure 4: A superficial analysis of keywords would probably assign this ticket to the IT Service Desk, as opposed to the Salesforce Admin group where it belongs.

Figure 4: A superficial analysis of keywords would probably assign this ticket to the IT Service Desk, as opposed to the Salesforce Admin group where it belongs.

To avoid the problem of information overload, service desk teams trying to automate triaging would have to guess which fields would be the most predictive of the right assignment group, ignoring critical data points. For instance, an ML model that only looked at the short description of the ticket above — ”more problems with browser and settings” — would never discover the employee’s intent: requesting Salesforce access. To find that intent, we must turn to BERT…

Transforming words into math

While understanding language doesn’t come as naturally to machines as it does to us, they compensate for it by being really, really, really good at math. In fact, BERT — a breakthrough technique we use to pre-train natural language understanding (NLU) models — has about 110 million parameters, while a larger version of BERT — fittingly referred to as BERT-Large — has 340 million. That’s slightly more parameters than there are seconds in an entire decade, and it’s almost exactly 340 million more numbers than the average person can remember (we start forgetting beyond seven).

This allows BERT to turn arbitrarily long strings of text into vectors with a standard length — in other words, to convert language into mathematical representations that can be manipulated, analyzed, and categorized. Central to BERT is another fittingly named machine learning concept, “attention,” which focuses the model on semantically important elements of the text, like the direct objects of verbs. Much like the human brain strengthens the connections between neurons that are frequently activated at the same time (“neurons that fire together wire together,” the saying goes), so BERT learns from millions of examples of which words and phrases are most correlated with the desired output, and then assigns them greater weight.

Confronted by the complexity of BERT and of deep learning in general, it’s easy to lose sight of the astounding big picture: we can now represent the meaning of a whole sentiment as essentially a single point in space. Of course, even small children can sort individual words along one dimension — say, by ranking foods like “cookie” and “broccoli” according to their sweetness. But mapping passages of text onto 1,024-dimensional hyperspace? That’s big.

The problem with small data

Despite these advances, it’s here that we reach perhaps the biggest obstacle standing in the way of automated ticket triage: the small data problem. In Part 1, we established that different companies face different IT challenges, and that machine learning usually isn’t effective without millions of training examples — more than any one service desk can provide. Even techniques as sophisticated as BERT aren’t equipped to learn from the handful of historical IT tickets relating to a particular issue at a particular company.

To overcome the problem of small ticket datasets, we need to augment the data. Moveworks takes a number of approaches to do so, and chief among these is collective learning, which uses tokenized ticket data gathered from many organizations to generate universal insights. Tokenization — the substitution of specific nouns like employee names and software packages with tokens like $PERSON and $SOFTWARE — protects the privacy of each organization while furnishing our ML models with tens of millions of IT tickets, enabling them to approach each new ticket with more “experience” than any human agent could.

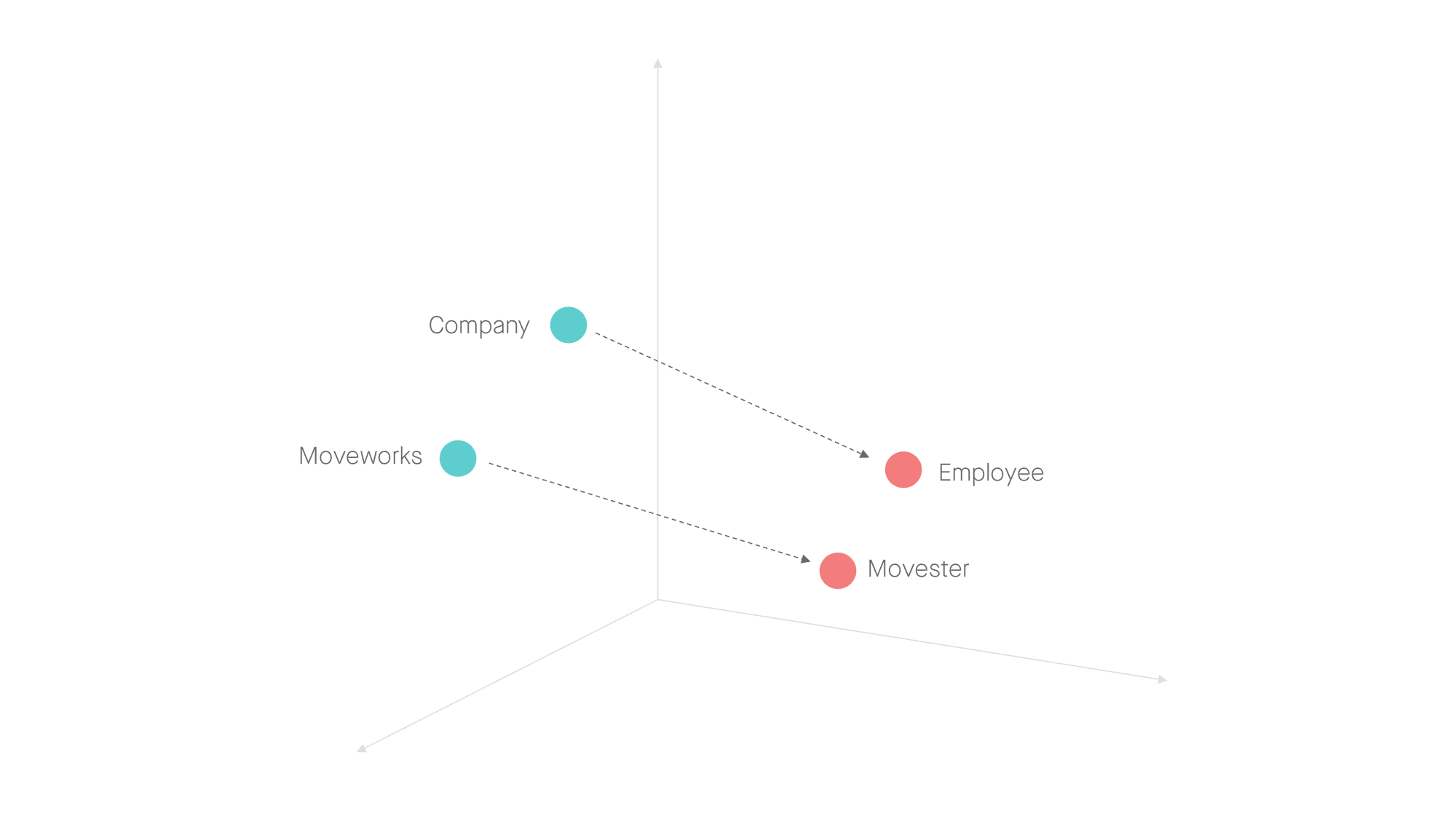

In order for this experience to be useful, however, the models must be able to generalize between tickets gathered from different companies by grouping analogous words by meaning. Moveworks does so by transforming the specific words that employees use to describe their IT issues into vectors known as word embeddings — learned representations of text where words that have similar meanings are given similar representations. For example, at Moveworks, we call every employee a “Movester,” so “Movester” would be linked to “Moveworks” in the same way “employee” would be linked to “company.”

Figure 5: Understanding the relationships between words allows Moveworks to generalize insights about syntax and semantics, despite the superficial differences between organizations.

Figure 5: Understanding the relationships between words allows Moveworks to generalize insights about syntax and semantics, despite the superficial differences between organizations.

A new era of IT ticket triage

With ML-powered triage, nearly every ticket is automatically routed, dramatically reducing the total time to resolution. The result has been a gigantic step change for employees and IT professionals alike.

Figure 6: Automated ticket triaging is finally a reality — and the technology is only getting better.

Figure 6: Automated ticket triaging is finally a reality — and the technology is only getting better.

Machine learning still has ample room to improve in the fast-evolving field of natural language understanding — the most significant breakthroughs to date have occurred in just the last few years. And no matter how advanced ML becomes, some IT tickets may never be resolved without a human touch. The key, then, is to ensure that every one of those tickets, no matter how convoluted, finds itself in exactly the right hands.

Contact Moveworks to learn more about how our deep learning automates ticket triage.